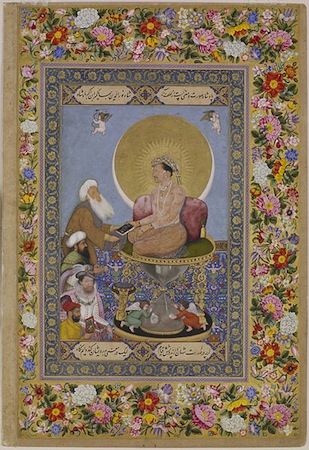

Jahangir Preferring a Su Shaikh to Kings

Jahangir Preferring a Su Shaikh to Kings. Bichitr. c. 1620 C.E. Watercolor, gold, and ink on paper.

- In this miniature painting, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings, flames of gold radiate from the Emperor’s head against a background of a larger, darker gold disc. A slim crescent moon hugs most of the disc’s border, creating a harmonious fusion between the sun and the moon, and symbolizing the ruler’s emperorship and divine truth.

- The Emperor is the biggest of the five human figures painted, and the disc with his halo—a visual manifestation of his title of honor—is the largest object in this painting.

- Jahangir faces four bearded men of varying ethnicity, who stand in a receiving-line format on a blue carpet embellished with arabesque flower designs and fanciful beast motifs.

- Below the Shaikh, and thus, second in the hierarchical order of importance, stands an Ottoman Sultan. The unidentified leader, dressed in gold-embroidered green clothing and a turban tied in a style that distinguishes him as a foreigner, looks in the direction of the throne, his hands joined in respectful supplication.

- The third standing figure awaiting a reception with the Emperor has been identified as King James I of England. By his European attire—plumed hat worn at a tilt; pink cloak; fitted shirt with lace ruff; and elaborate jewelry—he appears distinctive. His uniquely frontal posture and direct gaze also make him appear indecorous and perhaps even uneasy.

- Typically, at this time, portraits of European Kings depicted one hand of the monarch resting on his hip, and the other on his sword. Thus, we can speculate that Bichitr deliberately altered the positioning of the king’s hand to avoid an interpretation of a threat to his Emperor.

- Last in line is Bichitr, the artist responsible for this miniature, shown wearing an understated yellow jama (robe) tied on his left, which indicates that he is a Hindu in service at the Mughal court—a reminder that artists who created Islamic art were not always Muslim.

- During Mughal rule artists were singled out for their special talents—some for their detailed work in botanical paintings; others for naturalistic treatment of fauna; while some artists were lauded for their calligraphic skills. In recent scholarship, Bichitr’s reputation is strong in formal portraiture, and within this category, his superior rendering of hands.

- Clear to the observer is the stark contrast between Jahangir’s gem-studded wrist bracelets and finger rings and the Shaikh’s bare hands, the distinction between rich and poor, and the pursuit of material and spiritual endeavors.

- A similar principle is at work in the action of the Sultan who presses his palms together in a respectful gesture. By agreeing to adopt the manner of greeting of the foreign country in which he is a guest, the Ottoman leader exhibits both respect and humility.

- Finally, the artist paints himself holding a red-bordered miniature painting; He shows himself bowing in the direction of his Emperor in humble gratitude.