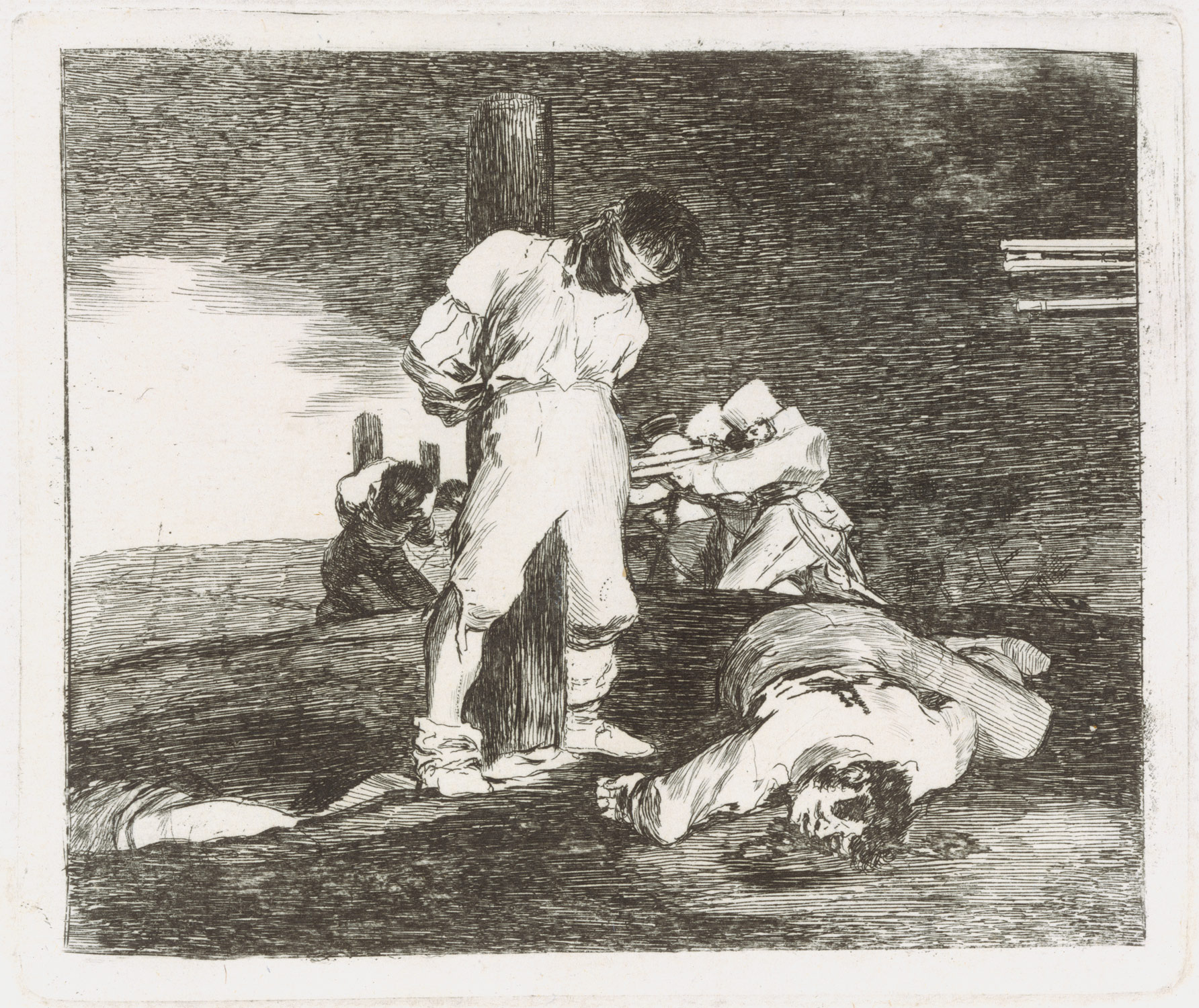

Yo no hai remedio (And There’s Nothing to Be Done)

Yo no hai remedio (And There’s Nothing to Be Done), from Los Desastres de la Guerra. Francisco de Goya. 1810-1823 C.E. Etching.

- A man, blind-folded, head downcast, stands bound to a wooden pole. Although the man’s off-kilter posture signifies defeat, he is yet heroic, an Alter Christus—another Christ.

- On the ground in front of him is a corpse, contorted, the spine twisted, arms and legs sprawled in opposite directions. His grotesque face looks out at us through obscured eyes as blood and brain matter ooze out of his skull and pool around his head.

- Other men, doubled-over and on their knees, are similarly secured to wooden stakes. To his right we see the cause of the carnage: a neat line of soldiers aim rifles at the men. The barrel of three rifles appear from the right edge of the picture, aimed at our messianic hero. Not only is he about to die, but his executioners are everywhere. There is nothing to be done.

- Francisco Goya created the aquatint series The Disasters of War from 1810 to 1820. The eighty-two images add up to a visual indictment of and protest against the French occupation of Spain by Napoleon Bonaparte. Soon, a bloody uprising, occurred, in which countless Spaniards were slaughtered in Spain’s cities and countryside. Although Spain eventually expelled the French in 1814 following the Peninsular War (1807-1814), the military conflict was a long and gruesome ordeal for both nations.

- Goya created his Disasters of War series by using the techniques of etching and drypoint. Goya was able to use this technique to create nuanced shades of light and dark that capture the powerful emotional intensity of the horrific scenes in the Disasters of War.

- Influenced by Spain's continuous warfare; famine and politics